Now Inventing Is Easier Than Ever!

By Norman Carlisle (1963)

Now inventing is easier than ever… Here’s how new materials, ready-made for the inventor, can start those royalty dollars flowing in.

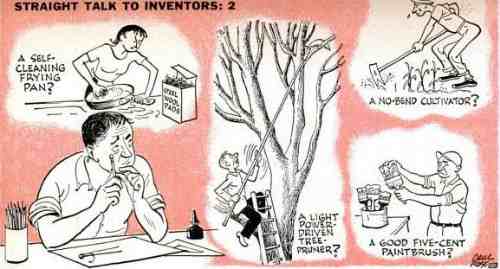

What’s happening to the independent inventor? Is he a dying breed, losing out in the face of competition from team research in the big industrial labs?

Not at all. The Patent, Trademark, and Copyright Research Foundation setting out to look into the whole business of who’s doing the inventing in America today, found that, in the past decade, 40 percent of all patents went to independents – men working alone. The Yankee ingenuity that has always made Americans the most innovative on earth is breaking out all over the place.

“The ranks of basement investors run a wider gamut than ever,”

was the way John Tigrett, perhaps America’s leading invention broker, put it to me. Among the 16,000 idea-getters Tigrett deals with each year, he lists lawyers, teachers, truck drivers, housewives, journalists, engineers, airline pilots, and business executives –a full occupational and educational spectrum.

Moreover, the inventions developed by individual inventors, most of whom have never seen the inside of a research lab, cover an impressive range, from tricky gadgets to processes that are changing whole industries.

Some have earned a few thousand dollars, some are bringing in royalties that run into millions. Inventing is not easy – there are problems that lie between the bright idea and the checks in the morning mail, among them the fact that it takes about three years to get a patent. But in many ways inventing is easier than it used to be.

Everybody’s in the act these days. Truck drivers, business executives, housewives, pilots – they’re all busy inventing new gadgets.

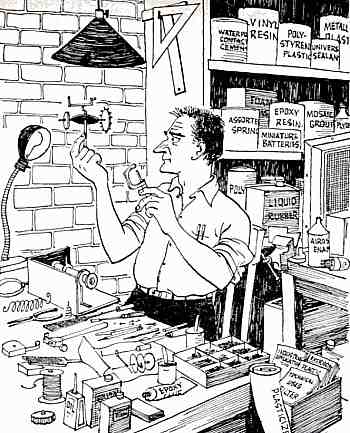

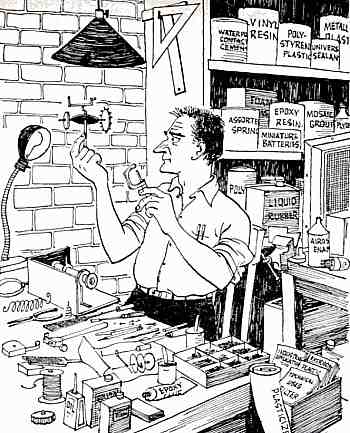

Whether you’re a weekend home workshop tinkerer or a trained technical man who chooses to go it alone, you’ve got factors working for you. Some areas, of course, are the almost exclusive province of big-lab research. You’re probably not going to develop another nylon, discover a new plastic, or make a portable reactor in your basement. But the very fact that team research is turning out so many new products – plastics, metal alloys, wonder chemicals, transistors, miniaturized batteries, and a host of other materials and devices – gives you new inventive opportunities.

I got dramatic evidence of how they’re being used by today’s independents when I investigated the experiences of more than 100 currently active, successful inventors.

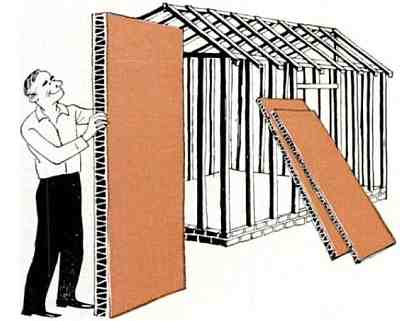

BUILDING A PAPER HOUSE

Take Harold Humes and his paper house. Humes, a writer with a technical turn of mind, didn’t have to invent the makings for his new kind of dwelling. That was done for him by chemists for the big concerns that turn out treatments for making paper water-, fire-, vermin-, and just about anything proof. When Humes got the idea that such paper would make a fine summer cottage or low-cost house for underdeveloped areas, all he had to do was design corrugated, honeycombed panels and work out a method of fastening them together with metal strips.

It took a lot of doing, of course, before Humes solved all the problems of making paper pillars, floors, and roofs – but he had all the ingredients and the help of the companies that manufacture them. The result is 27 different patents or patents applied for.

Huffing and puffing weren’t required to test inventor Harold Humes’ paper house. The work on the materials had already been done for him.

A Texan named Edwin Foster has struck it rich by finding new uses for the marvelous alloys of the steel metallurgists. Among his 50 recent patents are many for special steel springs, which Foster has found a way to coil. They are employed in such items as long steel tape rules (Foster’s springs are used in all that run over 12 feet) and the hose-retracting mechanism used on new gasoline pumps in service stations.

When an aluminum window got stuck, Foster figured that “there must be a better way to get this thing up.” There was. Foster did it with a ribbon of stainless steel, a device now widely used.

When Foster saw how easy it was for electric irons to get pushed off ironing boards or to be forgotten on them, he dreamed up another spring device. It lifts an iron off the board as soon as the user lets go. This invention, sold to a big appliance maker and now in production, took years of work on Foster’s part. But his job of making a spring that could lift when required to do so, but not resist the ironer, was made easier by the availability of the special type of steel used.

SCULPTURE IN A KIT

A new plastic resin brought New Yorker Charles Powell’s invention to reality. Powell had hit on an idea for making anyone a sculptor. There was nothing new about a figure assembled by joining pre-molded plastic components together. They had long been on the market. The trouble was that when you got them together they looked like what they were. Powell had a better idea: Let the person assemble the parts and then cover them with a material that would hide the joints. What kind of material? Powell didn’t know, but he thought that the answer was to embed small particles of wood, metal, or stone in some kind of paint like plastic that would set after application. He found a chemical company that made a vinyl resin that could serve as the binder he wanted. A ⅟16- to ⅟18- inch coating, applied with a brush, made a piece of sculptor look like the real thing. The sculpture was weighted by sand poured through an opening, which was covered by the coating.

Simple? Yes, but it was a patentable invention which, while it may not make Powell rich, will certainly give him a handsome return on his time.

In recent years a number of research labs have come up with new types of cement and glues = marvels of stickiness that will fasten almost anything to almost anything. They’ve been a boon to home craftsmen, industry, and amateur inventors.

James Severino of Encino, California, decided that the method of installing electrical conduits, receptacles, and outlets with nails, screws, or clamps was pretty crude. Why not cement them on? The system he devised is beautifully simple. The wiring units are coated with cement that stays sticky when covered with plastic. To install them, you just peel off the plastic covering and push the unit into place. There it stays, fastened for good. Patentable? It was, as patent No. 3,029,303 attests. Plastics are a happy medium for many independent inventors. Joseph Kitson of Connecticut was impressed with the marvels of polystyrene bubble-type plastic and with it invented a new form of building material. His patented discovery consists of a method of filling the bubbles with a fluid grout after panels of the plastic are in place in the building. He’s hit on a scheme that gives structural strength to a light, and easily handles the material.

SLEEPER

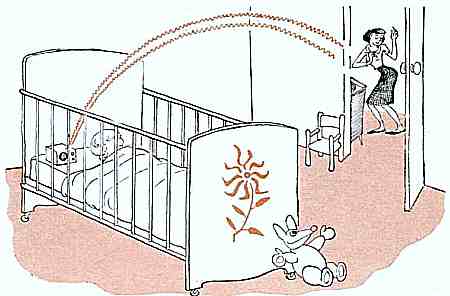

A Minnesota physician, Robert Horton, has the gratitude of many parents now getting a good night’s sleep. With the help of plastics, miniature batteries, and transistors, he invented a device that put squalling babies to sleep in a couple of minutes.

Noticing that babies are soothed by a humming noise, Dr. Horton tracked down the sound they like best—B flat. A few years ago he’d have been stumped by just how to make a gadget small enough and safe enough to utilize this discovery. It was no problem today. A buzzer that gives the right vibration, a tiny battery, a transistor to cut power demands and give it a 2,500-hour life, and a neat, smooth, plastic housing suitable for placing in a baby’s crib were the ingredients that gave the doctor his now widely sold Slumbertone.

The miniature battery that powers Horton’s baby-comforting buzzer is one of the hottest ready-made invention components ever to emerge from the big labs. Independent inventors have used them to power everything from pencil sharpeners to swizzle sticks. At least 100 battery-powered toys – games, tanks, planes, submarines, boats, and animals – are the brainchildren of freelancers.

Silencing the baby (without violence) is easy with a box that produces a steady B-flat hum. Transistors made invention possible.

COMBINING THE PARTS

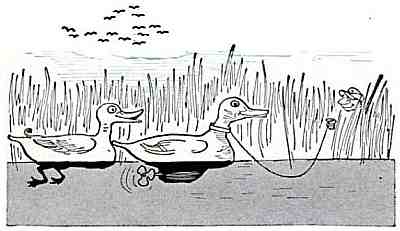

An invention that’s typical of the way inventors profitably team up peanut batteries and small electric motors is that of Ingle McAda of Wichita Falls, Texas. He took an ordinary duck decoy and installed a propeller shaft, a small electric motor, and a battery. His tethered duck decoy could thus be moved realistically. His patent is broad enough to cover plastic decoys of his own design, but McAda got a running start by using existing ones.

Invention for the birds: These mobile duck decoys with motors and propellor shafts use tiny batteries and motors on the market.

While new developments offer virgin territory, a lot of successful inventors advise: Don’t ignore older materials and devices. Plenty of opportunities await the alert amateur who is aware that big-business researchers can miss some pretty big bets.

Offhand, you’d hardly think there was any new way to exploit the small gasoline engine, yet Harry Leedom, a California engineer, found one. He evolved a unique wheel-power combination in which power from a small motor is delivered directly to a wheel by a belt running in a deep groove in the circumference of the rubber tire. Leedom’s powered wheels in various sizes, along with the forks and brackets that adapt them to everything from scooters to cultivators, are now in production.

NO PATENT PROBLEM

A question frequently asked by would-be inventors who would like to use ready-made parts is the one about patents. Isn’t it harder to get a patent on a device that utilizes components previously patented? The answer is no. An amendment to the patent law, passed in 1952, says, “Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor.” Furthermore, the definition of that word “process” is spelled out to include “a new use of a known process.”

Another practical question is “Where do you obtain the makings for an invention?” You’ve dreamed up something that calls for a particular kind of plastic – how do you find a manufacturer of the stuff you need?

The answer’s prettv simple. If you don’t find it on the shelves of your local hardware store, and you don’t see a suitable company listed in the telephone book, you turn to the inventor’s friend, Thomas’ Register of American Manufacturers.

If you live in a town of any size, your local public library is likely to have it. In its 9,030 pages you will find the names of everybody who makes anything. An index will lead you to the right page. You can then contact the manufacturer and get the names of dealers or suppliers, or such product information as you need.

HELP FROM MANUFACTURERS

This can be a wonderful lubricant to easing your invention along its way. Most companies, and all big ones, publish reams of technical literature, full of hints for inventors. For instance, Bakelite’s “Technical Release No. 12” gave (Charles Powell the information he needed about the company’s polymerized vinyl resin to make possible his do-it- yourself sculpture.

The help may go beyond printed literature to discussions with company technical representatives, especially if your invention gives promise of providing a sizable market for the company product.

“A technical reps” says Harold Hones, who estimates he talked to a couple of dozen of them in developing his paper house, “can be a gold mine of information for the inventor.”

Just how much company information can help an inventor is demonstrated by the experience of Michael Meyerberg, a New York theatrical producer who though American women deserved decent light to put on their make-up. Even in the theatre Meyerberg hadn’t seen a properly lighted make-up mirror. Fluorescent lights of low wattage around the mirrors didn’t provide enough light or distribute it right. Incandescent lamps of sufficient wattage were too hot; low-wattage incandescents didn’t give enough light.

Meverberg got in touch with GE. Sure company engineers told him, they had just the thing—a 15-watt lamp, with a special frosting inside, that gave a strong, diffused light but didn’t get hot.

“I had my invention made the minute I found out about that lamp,” he says.

He rigged up a compact, three-part mirror suitable for theatre or home use, mounting five of the bulbs on each post and four above the center mirror. That was all there was to it—but it won him a patent.

MORE DEVELOPMENTS ON THE WAY

One think is sure. The basement inventor isn’t going to run out of opportunity. Thermoelectric plates, to deliver power without batteries or outside source; new plastics like Delrin, which is tough enough to secure automobile parts; pinhead-size microphones that can make all kinds of mechanisms respond to the spoken command – the list of new developments that are almost wholly unexploited is growing daily.

Among them will you find the makings for your million-dollar invention?

[End of article]

Go From Now Inventing Is Easier Than Ever To Innovation Articles

Go From Now Inventing Is Easier Than Ever To The Home Page